I met Michael Engelhard in the Grand Canyon in 2012, when as one of our superb river guides he steered us capably through one massive rapid after another. In calmer waters our conversations took us through philosophy, anthropology, nature writing, and the importance of the wild. Michael’s naturalist expertise and characteristic deep thinking led me to want to stay in touch. He has recently published the marvelous book Ice Bear: The Cultural History of an Arctic Icon, which I highly recommend: it is beautifully written and illustrated, and engagingly conveys our complex relationship with this astounding creature, the Polar Bear, gorgeous and powerful. The following guest post, in honor of World Polar Bear Day on February 27, is by Michael, whose website is at this link.

Fig. 1. Study of a sleeping polar bear, by the English sculptor and painter John Macallan Swan, 1903. (Courtesy of Rijksmuseum Amsterdam)

These days, no animal except perhaps the wolf divides opinions as strongly as does the polar bear, top predator and sentinel species of the Arctic. But while wolf protests are largely a North American and European phenomenon, polar bears unite conservationists—and their detractors—worldwide.

In 2008, in preparation for the presidential election, the Republican Party’s vice-presidential candidate, the governor of Alaska, ventured to my then hometown, Fairbanks, to rally the troops. Outside the building in which she was scheduled to speak, a small mob of Democrats, radicals, tree-huggers, anti-lobbyists, feminists, gays and lesbians, and other “misfits” had assembled in a demonstration vastly outnumbered by the governor’s supporters. As governor, the “pro-life” vice-presidential candidate and self-styled “Mama grizzly” had just announced that the state of Alaska would legally challenge the decision of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the polar bear as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Listing it would block development and thereby endanger jobs, the worn argument went.

Regularly guiding wilderness trips in Alaska’s Arctic and feeling that my livelihood as well as my sanity depended upon the continued existence of the White Bears and their home ground, I, who normally shun crowds, had shown up with a crude homemade sign: Polar Bears want babies, too. Stop our addiction to oil! I was protesting recurring attempts to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the area with the highest concentration of polar bear dens in Alaska, to drilling. From the top of my sign a plush polar bear toy dangled, as if in effigy. Though wary of anthropomorphizing animals, I was not above playing that card.

Fig. 2. Greenpeace activist at London’s Horse Guards. The bear’s shape and behavior make it particularly suited for impersonations as part of political “theater.” (Courtesy of Elizabeth Dalziel/Greenpeace.)

As we were marching and chanting, I checked the responses of passersby. A rattletrap truck driving down Airport Way caught my eye. The driver, a stereotypical crusty Alaskan, showed me the finger. Unbeknownst to him, his passenger—a curly haired, grandmotherly Native woman, perhaps his spouse—gave me a big, cheery thumbs-up.

The incident framed opposing worldviews within a single snapshot but did not surprise me. My home state has long been contested ground, and the bear a cartoonish, incendiary character. Already in 1867, when Secretary of State William H. Seward purchased Alaska from Russia, the Republican press mocked the new territory as “[President] Johnson’s polar bear garden”—where little else grows.

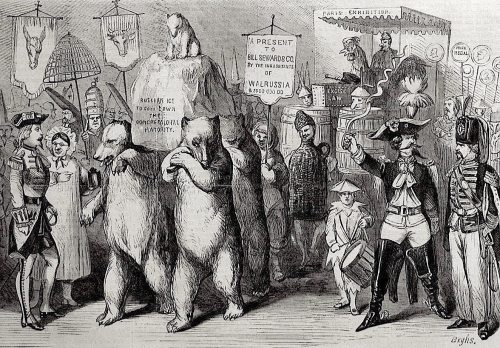

Fig. 3. This cartoon from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper lampooned the purchase of Alaska 150 years ago. The sign reads “A present to [Secretary of the Interior] Bill Seward & Co. by the inhabitants of Walrussia,” and polar bears carry an ice bloc to cool the congressional majority that ratified the treaty.

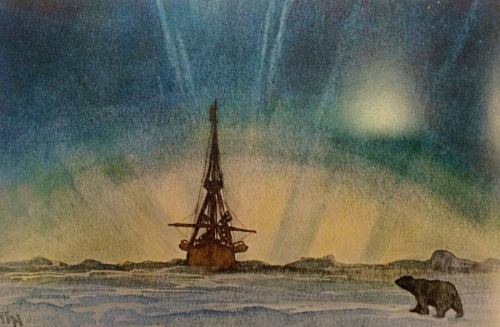

Fig. 4. Nomad of the sea ice and tundra. Norwegian postcard, 1915. (Collection of Michael Engelhard.)

Deeply held preconceptions keep us from seeing the true nature of some animals. The polar bear is a prime example. Over the past eight thousand years, we have regarded it as food, toy, pet, trophy, status symbol, commodity, man-eating monster, spirit familiar, circus act, zoo superstar, and political cause célèbre. We have feared, venerated, locked up, coveted, butchered, sold, pitied, and emulated this large carnivore. It has left few emotions unstirred. Where the bears’ negative image prevailed, as so often, a perceived competition for resources or a threat to our dominion were the cause.

Bears, and in particular polar bears, might not dwell in our neighborhoods but they do live in the collective consciousness. I have turned to this creature as other, in the words of ecologist-philosopher Paul Shepard, “in a world where otherness of all kinds is in danger, and in which otherness is essential to the discovery of the true self.”

Far from being intertwined exclusively with its Arctic indigenous neighbors, the polar bear has lately assumed iconic status in the dominant culture. With the wholesale domestication or destruction of wildness that marks industrial civilization, the polar bear has become a focus of our self-awareness, contentious as no other animal is. Its ascent from food to coveted curiosity to pampered celebrity may seem incremental, inconsequential even, but it speaks volumes about our relations with nature. Transferring polar bears—or their body parts or representations—into highly charged cultural contexts, we share in their essence and employ them for our own purposes.

In the wake of its first importation into Europe, the bear triggered scientific curiosity and inspired artworks and nationalistic myth building; it enlivened heraldic devices and Shakespeare’s plays; in naval paintings, it defined the self-image of a nation. On the eve of industrial revolution, Britain turned bear slaying into a symbol of manhood and expansionist drives. With the waning of Arctic exploration, the bear’s economic and even symbolic importance diminished. It was relegated to advertising, trophy hunting, or popular culture until, starting in the 1980s, conservationists promoted it as both an indicator of environmental degradation and also a symbol of hope. (Ironically, oil companies co-funded some of that period’s polar bear research, fulfilling government stipulations.) Where wildness is threatened the bear has been elevated. Its revived economic clout boosts films, fundraising campaigns, eco-merchandise sales, and high-end wildlife tourism.

My biggest surprise in my research has been the longevity of attitudes involving the polar bear, which is particularly striking in fast-changing countries such as ours. The bear is sometimes still a sexual predator or a “stud;” it still is protector, is killer, is idol; it can still serve as the embodiment of a nation, as figurehead for a group of people.

Fig. 5. Greenland’s coat of arms, showing the bear with its left forepaw raised, as it is thought to be left-handed, according to Eskimo lore. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

In gathering the stories and myths, the ideas and perceptions of many societies—including our own—I’ve sought to highlight the interplay of external and internal landscapes and the bear’s place in both. For the lore and awe it inspires, for the diversity and the sheer life force it adds to the world, I hope that the Great White Bear will continue to prowl both our internal and external landscapes for millennia to come.

Michael Engelhard is the author of the essay collection, American Wild: Explorations from the Grand Canyon to the Arctic Ocean, and of Ice Bear: The Cultural History of an Arctic Icon. He lives in Fairbanks, Alaska and works as a wilderness guide in the Arctic.

Thank you for this lovely post!

Great commentary. To lose this or any other majestic creature should leave a huge void in our hearts and must not be the legacy we leave our children.